This page provides an abridged history of the California Geological Survey. For a comprehensive historical account of the Survey, see Special Publication 126 - The California Geological Survey: A History of California’s State Geological Surveys, 1850-2015.

If you are looking for information about CGS Programs, please visit the CGS Programs page.

As might be expected for a state that owes its existence to the Gold Rush of 1849, the State Legislature recognized that geologists could provide valuable information about California’s mineral riches. In 1851, one year after California was admitted to the Union, the Legislature named Dr. John B. Trask, a medical practitioner and active member of the California Academy of Sciences, as Honorary “State Geologist” for his studies in the eastern Sacramento Valley. Dr. Trask heads a prestigious line of

California State Geologists.

In 1853 the Legislature passed a joint resolution asking Dr. Trask for geological information about the state. He was unofficially appointed State Geologist and was provided with a budget of $2,000. He submitted four geological reports which were highly valued by the Legislature, including, “On the Geology of the Sierra Nevada, or California Range”. By 1856 “Trask’s Survey” became dormant for lack of funding.

However, Dr. Trask had so impressed State officials with the value of his “California Geological Survey” that in 1860 the Legislature passed an act establishing the State’s first official

Geological Survey of California and, “to create the Office of the State Geologist, and to define the duties thereof.” The definition of duties included an accurate and complete geological survey of the State.

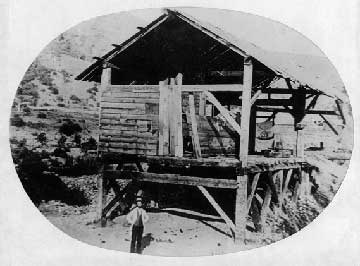

Sutter's Mill as it stood soon after its abandonment, 1853, Coloma, El Dorado County. Photo from CGS collection.

Sutter's Mill as it stood soon after its abandonment, 1853, Coloma, El Dorado County. Photo from CGS collection.

The act named Josiah D. Whitney (for whom Mount Whitney is named) to fill the new Office. A Yale graduate, Whitney had worked on several surveys in the eastern United States, including the New York Survey under the most noted geologist of his day, James Hall. Whitney’s appropriation was $20,000. He was a leading geologist in the United States and the foremost advocate of geological research of his time. He soon recruited a competent, well-rounded staff of young specialists with William H. Brewer as field geologist and Clarence King as a volunteer reconnaissance geologist. King later, in 1879, became the first Director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Unfortunately, Whitney’s first very learned works were on the State’s paleontology and its flora and fauna, when the State Legislature wanted information on gold resources. Whitney’s crusty and sometimes abrasive nature did not serve him well when he later insulted the Legislature and Governor Newton Booth in his disappointment over budget cuts to the Survey. The inevitable result was the abolishment of funding for the Whitney Survey in 1874; however, in 1879 and 1880, Whitney published two great Survey volumes on the auriferous gravels of the Sierra Nevada with his own funds.

Replacing the Geological Survey of California in April 1880 was the newly established California State Mining Bureau created by Legislative action in a bill sponsored by the Honorable Joseph Wasson. The establishment of the Bureau was a direct action in response to the need for information on the occurrence, mining, and processing of gold in the State. Its focus was on the mining industry, and the Governor appointed a State Mineralogist to head the Bureau. Although the State Mineralogist reported directly to the Governor, in 1885 a five member Board of Trustees was created to advise the State Mineralogist on various policy issues. The Board of Trustees eventually became today’s

State Mining and Geology Board.

In 1891 the State Mining Bureau published the first geologic map of the State (Preliminary Mineralogical and Geological Map of the State of California) showing eight stratigraphic units in color, along with numerous blank areas where information was lacking. The second colored geologic map of the State, published in 1916, showed 21 stratigraphic units and was accompanied by an explanatory volume (Bulletin 72, Geologic Formations of California.)

In 1927 the Bureau became the

Division of Mines, and was placed into the Department of Natural Resources. In 1928, with the hiring of the first geologist since the original Survey, focus of the Division began to shift towards the gathering of basic geologic information. By 1938 a new 1:500,000-scale geologic map was published.

Woman using a rocker at the Kendon Pit placer mine, 1930, Mono County. Photo from CGS collection.

Woman using a rocker at the Kendon Pit placer mine, 1930, Mono County. Photo from CGS collection.

During the 1940’s and 1950’s, the Division developed as a state geological survey and two well-defined branches were established: the Mining Engineering Branch and the Geology Branch. The Division began processing numerous geological quadrangle maps and reports for publication. In 1952 the Division conducted its first public-safety related effort by documenting the impacts of the 1952 Arvin-Tehachapi earthquake (Magnitude 7.3).

The 1960’s were years of development of new programs and a modernization of long-standing programs. In 1962, the

Division of Mines was renamed the

California Division of Mines and Geology (CDMG). The Division’s focus had shifted from an organization that was primarily mine-oriented to one responsible for a broader range of practical applications of geology, especially geologic and earthquake hazards. A highlight of the decade was the completion in 1966 of the

California Geological Atlas series.

(Related: trace the early evolution of the California Geological Survey in

Genealogy of California State Departments of Natural Resources and Conservation 1870-1970)

From the early 1970’s to the present, Division programs have expanded, often because of the passage of legislation. Following damaging earthquakes and landslides during the 1970’s and 1980’s, legislation was enacted that clearly focused CDMG’s authority on several fronts, including:

- Establishing the Strong-Motion Instrumentation Program (1971) to obtain statewide records of the response of rock, soil, and structures to ground motions caused by earthquakes. This program received national recognition in 2006 as the “Top Seismic Program of the 20th Century”.

- Enacting the Alquist-Priolo Special Studies Zones Act (1972), mandating the delineation by the State Geologist of zones along the surface traces of recently active faults, and the prohibition of construction of buildings for human occupancy across the surface trace of active faults.

- Enacting the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act (1976) to ensure that significant mineral deposits are identified and protected and the reclamation of mined lands is performed in accordance with uniform state standards.

- Enacting the Seismic Hazards Mapping Act (1990) that established a program to identify, map and zone seismic hazards.

- Legislation declaring that the Department of Conservation is the primary state agency responsible for geologic hazard review and investigation (Public Resources Code Section 2211).

Additional legislative language was also added to various statutes that defined the Survey’s responsibilities as encompassing:

- Identification and mapping of geologic hazards, and estimates of potential consequences and likelihood of occurrence.

- Information and advisory services including maintenance of a geologic library, public education program, maintenance of a geologic data base, review functions, and expert consulting to federal, state and local government agencies.

- Emergency response including monitoring and assessment of anomalous geologic activity, and operation of a clearinghouse for post-event earth science investigations.

- Development and application of hazard mitigation methods, including identifying state research needs, facilitating needed research, and expediting the application of new research results to public policy.

Reflecting the relevancy of its evolving and diverse programs in applied geology, in August 2006 the State Legislature changed the Survey’s name from the

Division of Mines and Geology to the

California Geological Survey – thus coming full circle in recognizing its origins in the Trask and Whitney surveys.